Uncategorized

The WPA and Its Lasting Impact on Art and Design in the United States

The Works Progress Administration (WPA), founded in 1935 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, was created in response to the devastating unemployment of the Great Depression. Its purpose was clear: put Americans back to work and restore a sense of dignity and productivity during an economic crisis. Among its most innovative branches was the Federal Art Project (FAP), which provided employment for artists across the country. Beyond jobs, the program transformed the role of art in American life—making it accessible to everyday people and embedding it in public spaces. In doing so, the WPA redefined not just who could be an artist, but making art accessible to everyone.

The Federal Art Project (FAP)

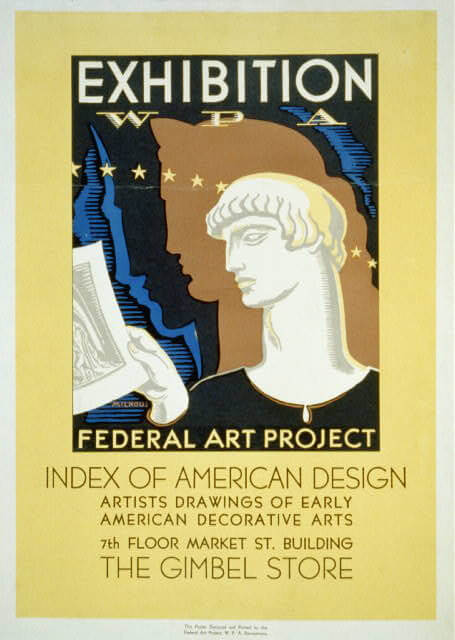

The Federal Art Project, under the WPA, was unprecedented in scale and vision. It employed over 5,000 artists and produced more than 200,000 works of art between 1935 and 1943. Murals, sculptures, easel paintings, and posters were placed in post offices, schools, libraries, and government buildings, reaching audiences who had never before experienced art in their daily lives. At its heart, the FAP was a cultural democratization effort: art was no longer confined to elite galleries and collectors, but was brought into the spaces of everyday Americans.

An Inclusive Culture

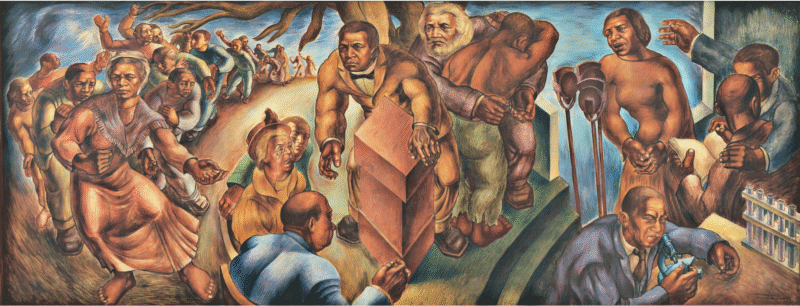

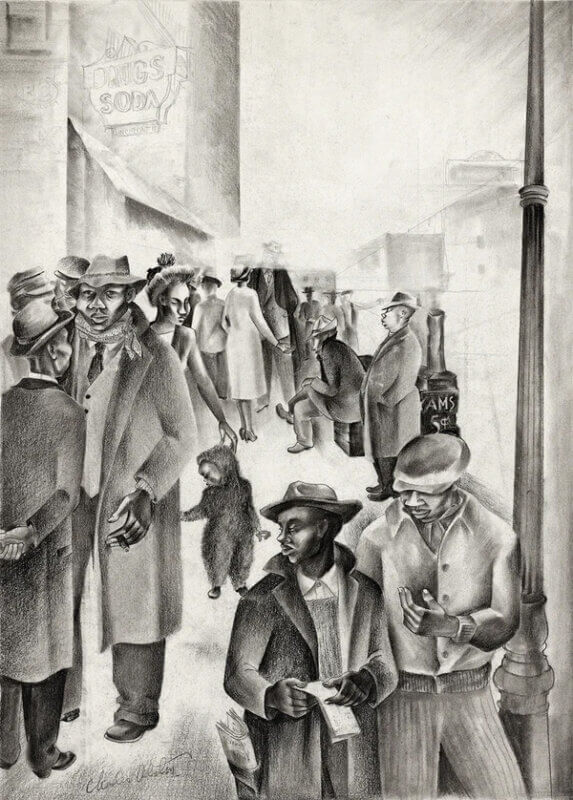

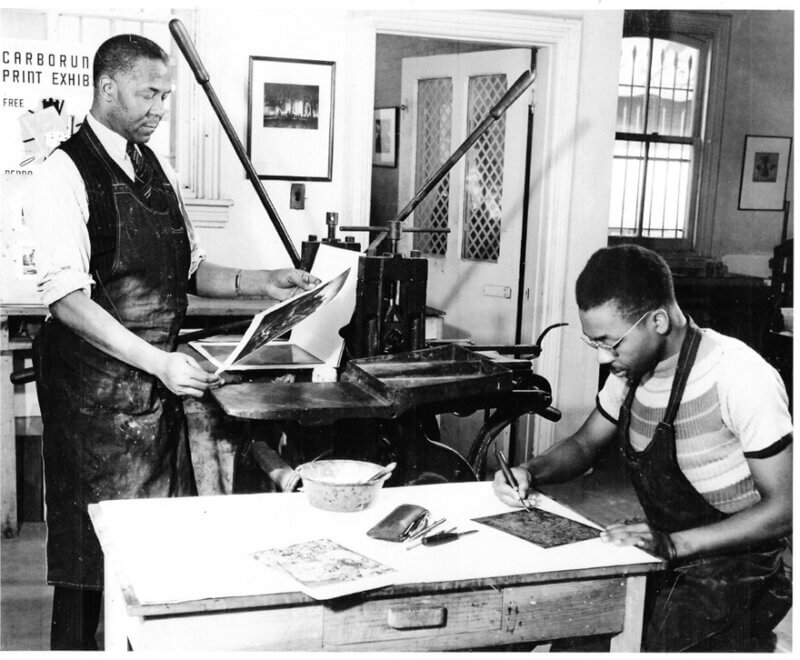

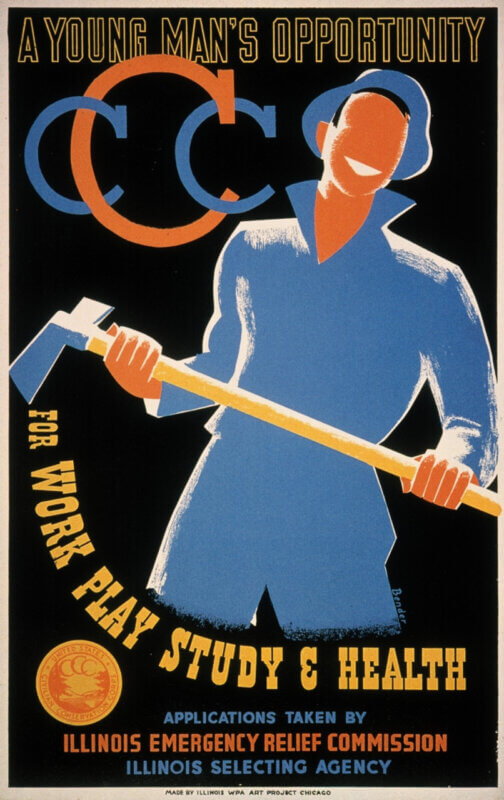

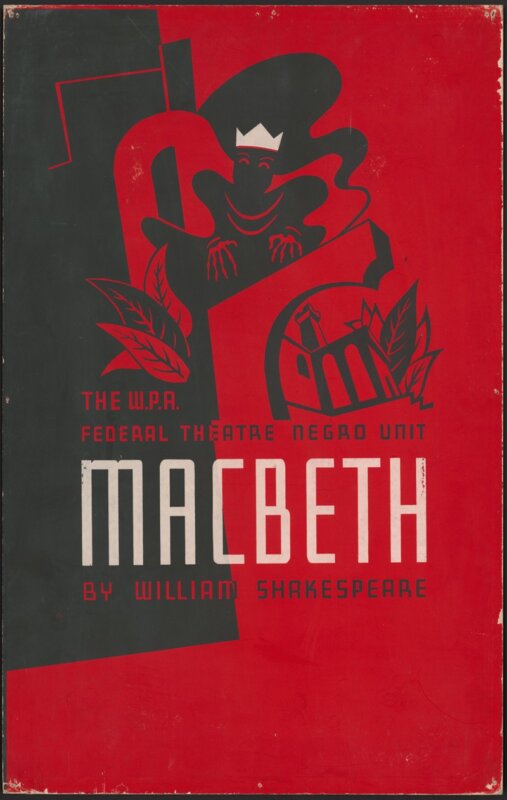

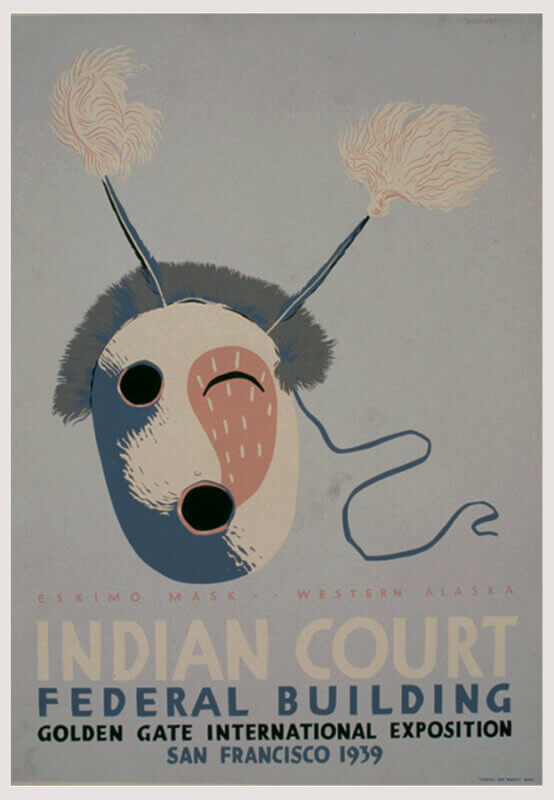

The WPA was credited with bringing art into everyday life and giving opportunities to artists who had been excluded from elite circles. African American, Native American, immigrant, and women artists found a place in these programs, and their voices became part of the national story.

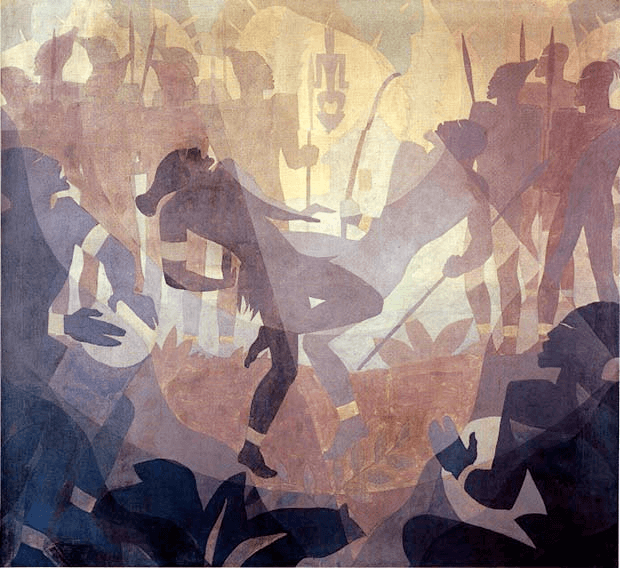

One of the WPA’s most groundbreaking contributions was its commitment, though imperfect, to inclusion of all Americans. African American artists such as Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage, Aaron Douglas, and Charles Alston were given opportunities to work, teach, and exhibit in ways that had previously been denied to them. Harlem became a hub for WPA projects that celebrated Black culture and history, contributing to what became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

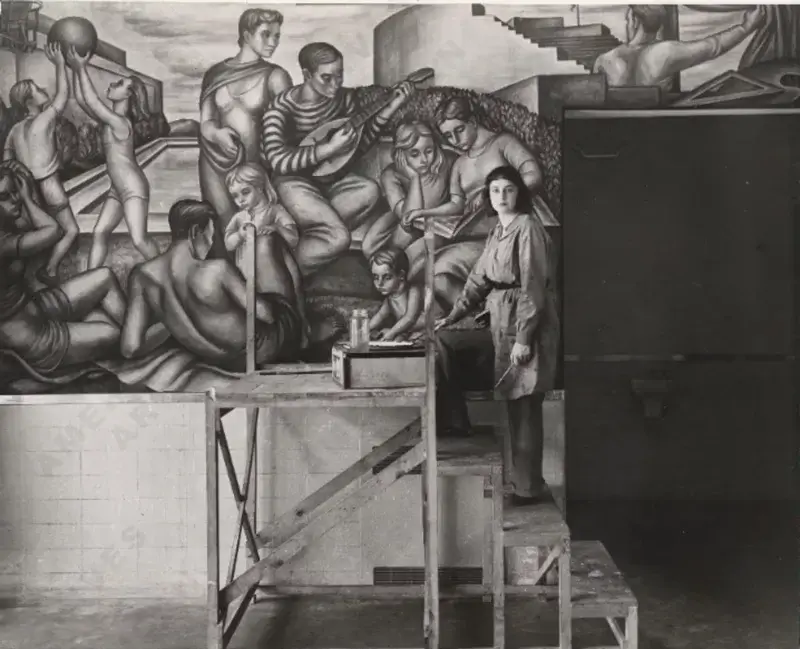

Women artists, too, found a place in the program. Though often overlooked, figures such as Lucienne Bloch and Elizabeth Olds left lasting marks in muralism and printmaking. The WPA also reached into small towns, rural communities, and immigrant neighborhoods, ensuring that art reflected the diverse voices of America. While segregation and systemic barriers persisted, the WPA was more inclusive than any federal art initiative before it.

Notable Artists and Examples

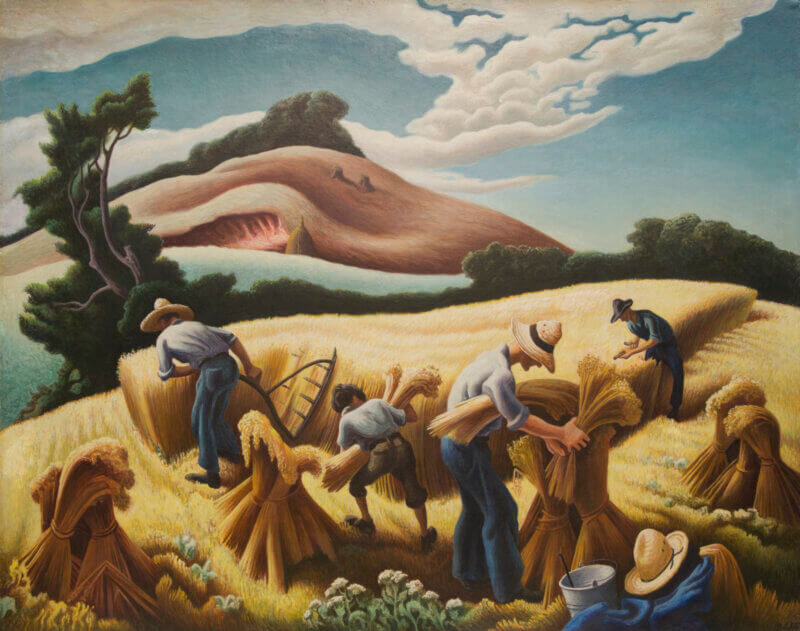

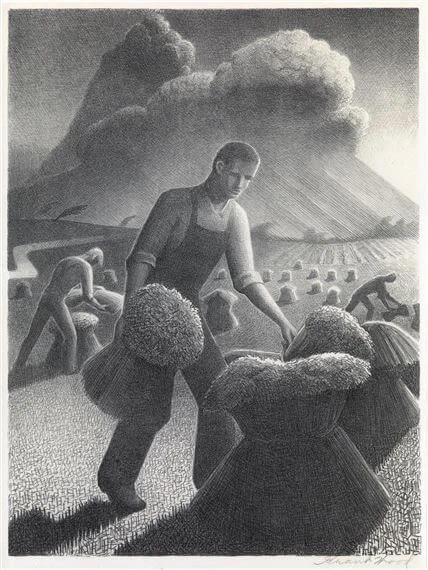

Regionalist painters like Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton captured the heart of rural America, while Social Realists such as Ben Shahn depicted workers, strikes, and the struggles of everyday life. The WPA served as a springboard for many artists who went on to shape American art.

Jacob Lawrence, who began working with the WPA at a young age, later became one of the most important African American painters of the 20th century. Sculptor Augusta Savage not only created monumental works but also trained a new generation of Black artists.

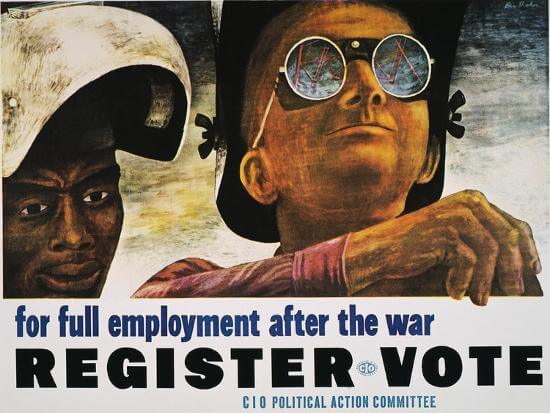

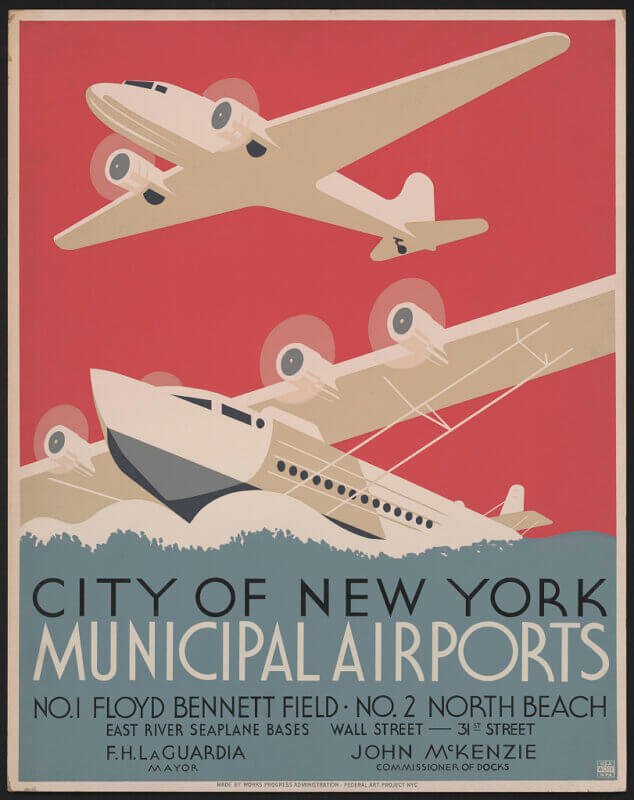

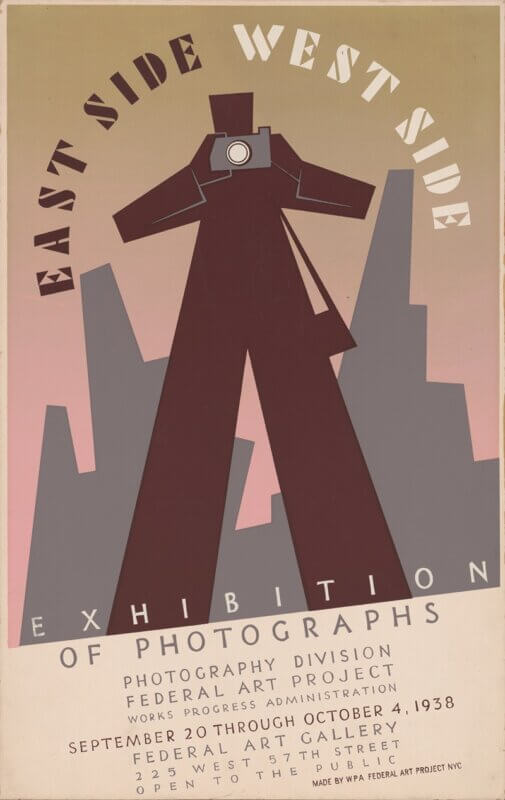

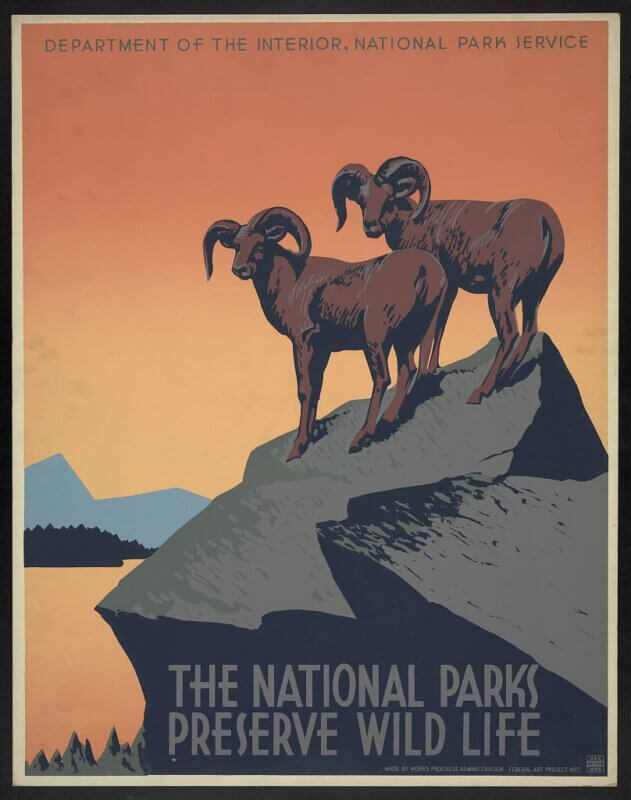

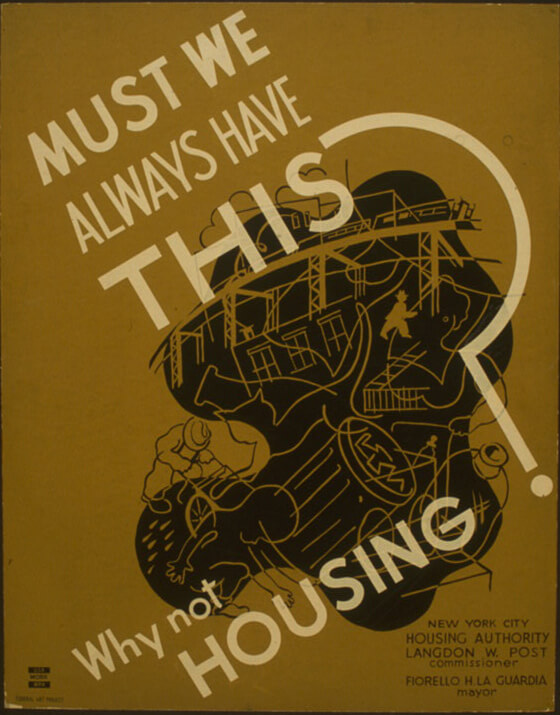

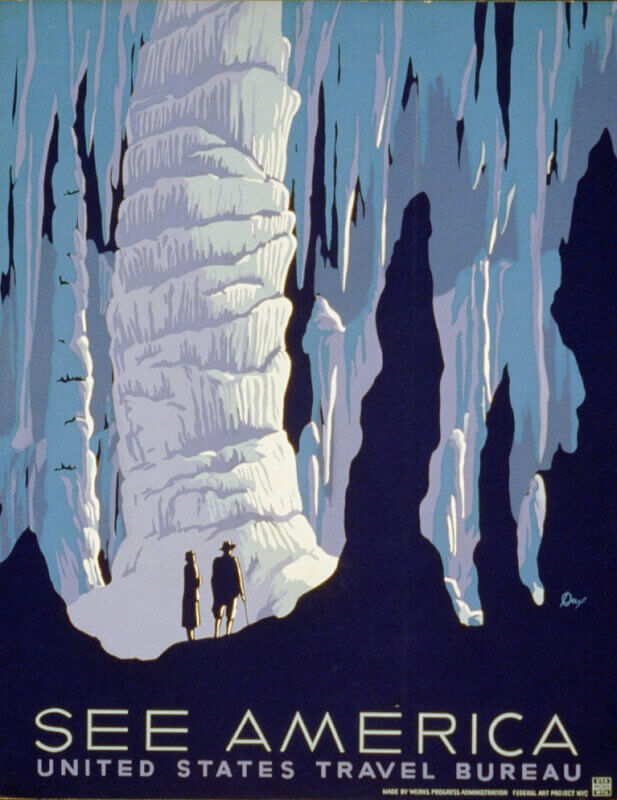

Beyond painting and sculpture, the WPA produced striking poster designs that promoted literacy programs, health campaigns, and America’s National Parks. These posters, with their bold colors and simplified forms, remain iconic examples of functional design.

Graphic design played a huge part in civic messaging. The posters supported a wide variety of public service messages, reflecting the New Deal’s priorities:

- Arts & Culture – Promoted theater performances, concerts, art exhibits

- Education & Literacy – Encouraged reading, library use, school attendance

- Conservation – Promoted national parks, soil conservation, tree planting

- Health & Hygiene – Advised on disease prevention, cleanliness, nutrition

- Work & Citizenship – Advocated civic responsibility, labor rights, and job training

- Events & Campaigns – Posters for voting drives, festivals, safety awareness

Style and Design

- WPA posters are known for their bold, graphic style, which often drew from:

- Art Deco

- Modernism

- Bauhaus-inspired typography

- Simplified shapes and vibrant color palettes

Notable poster artists included:

- Anthony Velonis – credited with introducing silkscreen to the FAP

- Richard Floethe – national art director of the WPA poster division

- Vera Bock

- Katherine Milhous

- and many others

Where the art was displayed

- Most posters were hand-designed by artists employed by the Federal Art Project and then reproduced. Usually, screen-printed (a relatively new and cost-effective process at the time) or lithographed in large quantities and distributed to:

- Schools

- Libraries

- National parks

- Health departments

- Theaters

- Community centers

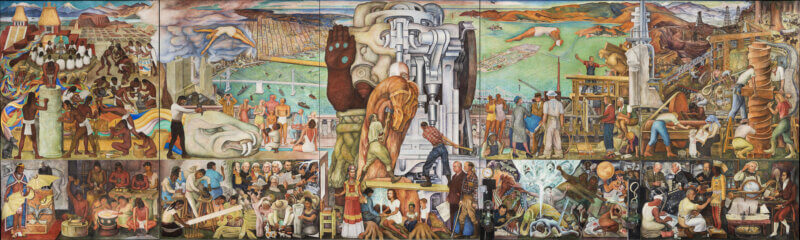

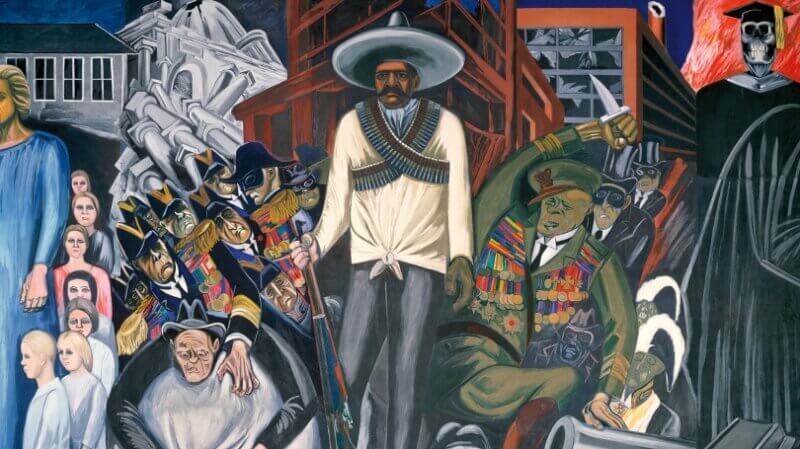

Influence of Mexican Muralists

The WPA’s vision for muralism owed much to the example of Mexican artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Though Rivera himself was not part of the WPA because his politics and nationality made him too controversial. His large-scale murals in Detroit and New York inspired a generation of American muralists. Rivera’s focus on workers, industry, and social themes resonated with WPA goals. U.S. artists borrowed his methods and adapted them to the American context, creating murals that celebrated national history, local culture, and the dignity of labor.

Public Reception and Legacy

For many Americans, WPA art was their first direct encounter with professional painting, sculpture, or design. The presence of murals in post offices and schools meant that art was no longer a distant or elitist pursuit—it was part of daily life. The public began to see art as something that could educate, inspire, and build civic pride. This shift in perception was one of the WPA’s most enduring achievements. It planted the idea that art is not a luxury, but a public good.

Lasting Influence on today’s Art & Design

The WPA’s legacy extends far beyond the 1930s. Its bold, graphic poster designs influenced mid-century modernism, the Swiss design movement, and today’s digital flat design. Its murals inspired the growth of community art projects in the 1970s and 1980s, and continue to shape the aesthetics of street art and social practice art today. The emphasis on accessibility and inclusion paved the way for institutions like the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). In many ways, the WPA established the foundation for thinking about design as functional, civic, and for the people. The idea that art should be woven into the fabric of public life—schools, transit systems, parks—remains a defining principle of American design and cultural policy.

The WPA has influenced a lot of what we know today about art and design. It created:

- Visual Time Capsule: They provide a powerful window into American values and concerns during the 1930s and early ’40s.

- Graphic Design Legacy: WPA posters helped define a uniquely American graphic style and influenced mid-century poster design.

- Public Art Model: Demonstrated how design can effectively serve the public good.

A visual timeline showing how the WPA’s design style and philosophy spread into later decades is a follows:

- 1935–1943 (WPA Posters): Bold colors, simple type, art for the public

- 1950s–1960s (Modernist Design): Swiss style, clarity, grids, sans-serif

- 1970s–1980s (Public Signage): Transit systems, wayfinding, National Park branding

- 1990s–2000s (Community Murals): Local pride, grassroots, representation

- 2010s–Today (Flat Design & Street Art): Minimalist digital design, inclusive public art, street aesthetics

The WPA was more than an economic relief program; it was a cultural revolution. By employing artists of diverse backgrounds, encouraging public accessibility, and drawing inspiration from global influences, it reshaped the American artistic landscape. Its effects are still visible today in the murals that line our communities, the graphic clarity of public signage, and the belief that art and design belong to everyone. Not all WPA art was labor-focused — some depicted landscapes, history, or abstract themes — but the overarching spirit was art in service of the people, not art as luxury.In a time of hardship, the WPA reminded the nation that creativity, like food or shelter, is a necessity—not a luxury—and that art can help define and strengthen a democracy.

References

- Many WPA posters are digitized and viewable online through:

Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Library of Congress) - Museums like the Smithsonian

- MoMA often feature them in exhibitions.

Bearden, R., & Henderson, H. (1993). A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present. Pantheon Books.

Cockcroft, E., Weber, J., & Cockcroft, J. (1998). Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement. University of New Mexico Press.

Enyeart, J. (1987). The WPA Federal Art Project: Posters for the People. Library of Congress.

Fine, E. H. (1974). The Afro-American Artist: A Search for Identity. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

McKinzie, R. D. (1973). The New Deal for Artists. Princeton University Press.

Melosh, B. (1991). Engendering Culture: Manhood and Womanhood in New Deal Public Art and Theater. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Mavigliano, G. (1984). “Public Attitudes Toward WPA Art.” American Quarterly, 36(2), 211–230.

O’Connor, F. V. (1972). Art for the Millions: Essays from the 1930s by Artists and Administrators of the WPA Federal Art Project. New York Graphic Society.

Park, M., & Markowitz, G. E. (1984). Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal. Temple University Press.

Quinn, R. (2017). Design for Democracy: The History and Future of Public Interest Design. Routledge.