Uncategorized

Uncovering the Magic: Authenticating My Early 1900s “Carter the Great” Lithograph

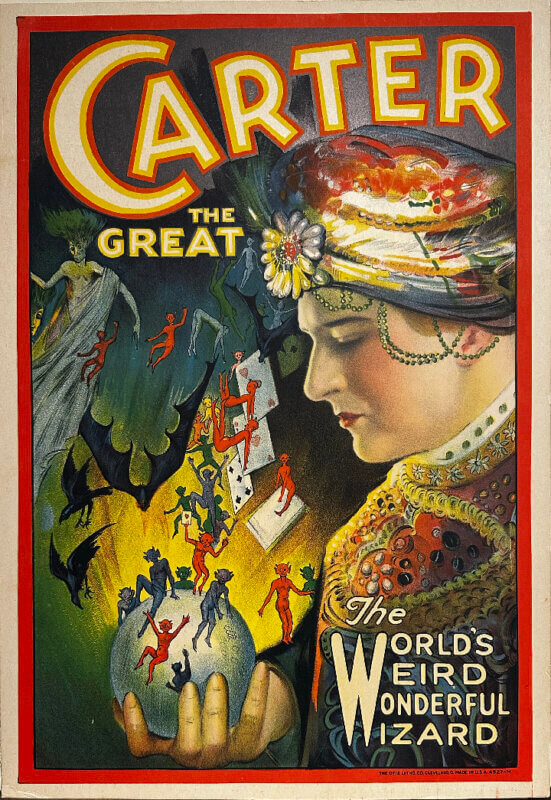

Authenticating My Early 1900s “Carter the Great” Lithograph was great fun, comparing the find as if I stubbled upon a hidden treasure. There’s a special kind of thrill that comes from uncovering a piece of printmaking history. That’s exactly how I felt when I discovered an original Carter the Great poster at Cotton’s Antique Emporium in Pueblo, Colorado.

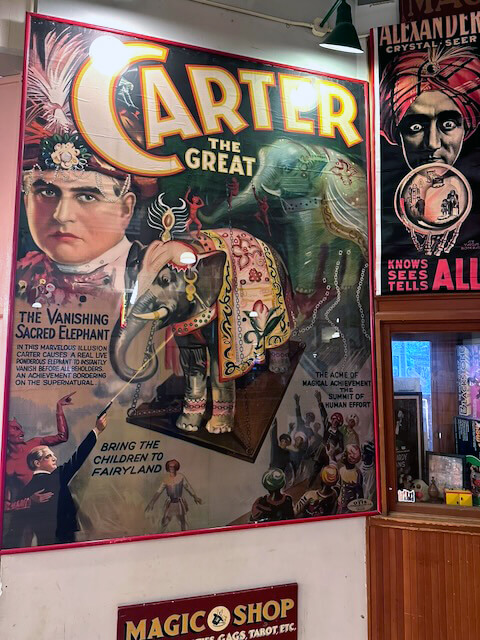

The store itself was massive, nestled in Downtown Pueblo. I visited there during the lively Chile and Frijoles Festival, which happens every September. The atmosphere was festive, the streets were crowded, and everyone seemed to be having a great time. I had seen a version of this same poster years before — a wall-sized reproduction near Seattle’s Pike Place Market — and the vibrant colors had always stuck with me. But I never expected to come across what might be an actual early 20th-century lithograph.

As a creator, designer, and collector of vintage posters, finding an original stone lithograph from the early 1900s is absolute gold. Naturally, I asked about its origins. One of the shop owners shared that it had been purchased at an estate sale back in the 1990s. That was a promising detail — high-quality fine-art reproductions existed then, but widespread commercial giclée printing didn’t take off until the early 2000s. Still, I stayed cautious.

I inspected the print closely using a loupe and the zoom on my iPhone 14, checking for signs of commercial offset printing or inkjet reproduction. It passed the size test typical of early theater window posters. And one of the biggest tells — the back of the paper — showed aged, uncoated stock with ink marks and imperfections. A modern fine-art reproduction would have a bright, clean white back (see my article on fine art printing). The poster was framed tightly, so I could only assess what was visible, but everything looked promising. Trusting my research — and the shop owner — I purchased it.

After bringing it home, I wanted to understand not only its visual details, but how it was made. That’s when I dove deeper into the history of stone lithography and the remarkable era of early theatrical poster printing.

The Art of Stone Lithography in the Early 1900s

Long before offset presses took over, stone lithography was the heart of commercial poster printing. This painstaking, handcrafted process produced the rich, saturated colors that now define classic magic, circus, and vaudeville posters.

How Stone Lithography Worked

- An artist drew directly onto a smooth limestone slab using greasy crayons or ink.

- The stone was treated chemically so that non-image areas absorbed water.

- Oil-based ink adhered only to the drawn areas.

- Paper sheets were pressed onto the stone — one at a time.

- Each color required its own stone and had to be aligned carefully by hand.

This created:

- Lush, layered color

- Slightly textural, painterly surfaces

- Subtle variations from print to print

- A rich depth impossible to replicate with modern digital methods

These qualities remain key to authenticating early lithographs today.

Otis Lithograph Company: Cleveland’s Printing Powerhouse

During the golden age of American poster art, the Otis Lithograph Company of Cleveland, Ohio, became famous for producing some of the most vivid, detailed, and dramatic posters of the 1910s–1920s.

Otis specialized in:

- Theatrical and vaudeville posters

- Magic and illusionist imagery

- Window cards

- Circus-style illustration

- Early film and commercial advertising

Although many artists went uncredited, the craftsmanship is unmistakable. Museums and archives today list numerous Otis posters — including magician posters — as verified stone lithographs.

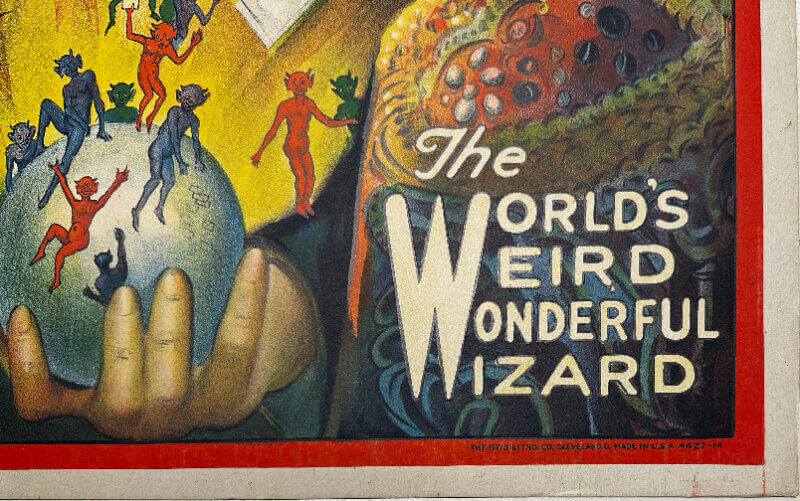

For collectors, seeing the Otis credit line is a strong sign of period authenticity.

How I Evaluated My Poster’s Authenticity

Once I had a better understanding of early lithography and Otis’s importance, I began examining my own Carter the Great poster with more intention.

1. Provenance

Recent ownership is clear:

- Purchased at an estate sale in the 1990s

- Later acquired by Cotton’s Antique Emporium

- Purchased by me afterward

Provenance alone doesn’t authenticate a piece, but it supports the case when combined with physical evidence. (Article on Provenance)

2. Printer’s Credit

Many originals include a small imprint such as:

“Otis Litho Co., Cleveland”

This typically appears along the bottom margin or just inside the border. If present, it becomes one of the strongest attribution markers.

3. Ink Texture Under Magnification

Using magnification, I checked for:

- Continuous tone, without halftone dots

- Crayon or tusche textures from hand-drawn litho work

- Layered ink buildup visible under light

Stone lithographs never use mechanical dot patterns — a dead giveaway of offset printing.

4. Paper & Wear Patterns

Authentic early-1900s posters typically show:

- Age toning (not bright white)

- Light fading

- Edge wear

- Slight brittleness

- Random ink marks or imperfections from printing

Mine showed ink transfer on the back and small front blemishes — signs consistent with original lithographic production.

Because the poster was reportedly stored unused, it lacked tack holes or heavy wear.

How to Authenticate Your Own Magic Poster

A guide for collectors, designers, and curious historians

Whether you’re evaluating a Carter, Thurston, Blackstone, or other magic-era poster, here’s a streamlined approach:

Step 1 — Look for a Printer’s Imprint

Common authentic printers include:

- Otis Litho Co. (Cleveland)

- Strobridge Litho Co. (Cincinnati)

- Erie Litho & Printing Co.

- Russell-Morgan

Check the lower margin or bottom corners.

Step 2 — Inspect with a Loupe

Use a 10× magnifier to check for:

- No halftone dots

- Visible crayon strokes or organic lines

- Ink layering or minor color misalignment

If you see perfectly spaced dots → modern offset printing.

Step 3 — Examine the Paper

Authentic paper usually shows:

- Natural age toning

- Visible fibers

- Slight brittleness

- Pressure impressions from printing

Bright white, smooth paper is nearly always modern.

Step 4 — Identify Use-Related Wear

Originals often show:

- Tack holes

- Tape remnants

- Display fading

- Edge abrasions

Not all originals have these — especially unused stock — but when present, they support authenticity.

Step 5 — Compare With Museum and Auction Archives

Look up:

- Carter the Great posters

- Thurston magician posters

- Otis Lithograph archives

- Auction results (Potter & Potter, Haversat & Ewing)

Matching colors, layout, and dimensions can be strong evidence.

Step 6 — Get an Expert Review

A paper conservator can analyze:

- Paper fibers

- Ink chemistry

- Age markers

This provides the highest level of verification.

Why Authenticity Matters

A true stone lithograph is more than a poster — it’s a handcrafted artifact from a golden age of stage magic. It represents:

- Forgotten craft techniques

- Early commercial printmaking

- Touring magic culture

- American advertising history

My Carter the Great poster bridges the past and present, carrying its own story through every ink layer, fiber, and imperfection. And now, with a clearer understanding of its origin, I can share that magic with others.

Read more about Charles Joseph Carter (Carter the Great).